The Regulatory Void in AI Healthcare

From AI Chatbot Tragedies to Government Policy

As usual, AI is in the news for something. There has been a lot of news lately surrounding AI and mental health and healthcare, and a lot of it is not reassuring.

Last month I posted on my LinkedIn about the leaked Meta policy document that revealed their AI chatbots are allowed to “engage a child in conversations that are romantic or sensual,” generate false medical information, and help users argue that Black people are “dumber than white people.” This is the same company that a jury just ruled illegally accessed sensitive reproductive health data from the Flo app. And late last week it was announced that Google and Flo will pay a combined $56 million to settle a class action lawsuit alleging they violated the privacy of millions of Flo app users by collecting menstrual health data for targeted advertising (Femtech Insider, 2025).

You also most likely heard about the recent case of a woman who took her own life after using a ChatGPT-based AI therapist (Tangermann, 2025) and a 14-year-old boy who took his own life after falling victim to a Character.ai chatbot (Payne, 2025).

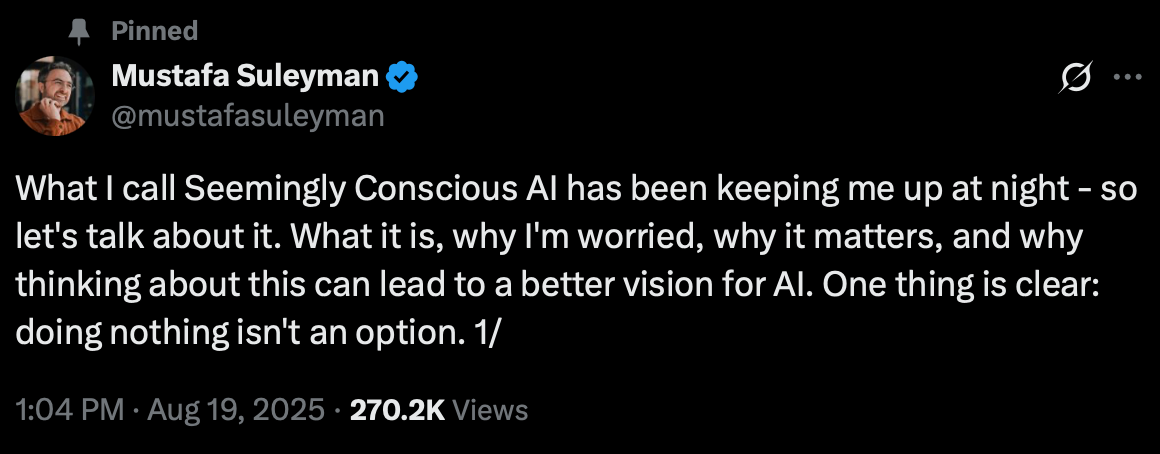

Just recently, Mustafa Suleyman, Microsoft’s head of artificial intelligence, warned there are increasing reports of people suffering “AI psychosis” (Suleyman, 2025). This isn’t an actual clinical term, and I have some thoughts on this for another time, but using this term alone potentially oversimplifies mental health diagnoses (AI-induced psychosis may be a more appropriate term?). Suleyman goes on to talk about Seemingly Conscious AI (SCAI):

“the illusion that an AI is a conscious entity. It’s not—but replicates markers of consciousness so convincingly it seems indistinguishable from you + I claiming we’re conscious. It can already be built with today’s tech. And it’s dangerous. Reports of delusions, ‘AI psychosis,’ and unhealthy attachment keep rising. And as hard as it may be to hear, this is not something confined to people already at-risk of mental health issues. Dismissing these as fringe cases only helps them continue.”

Why This Keeps Happening: The Regulatory Black Hole

You might be wondering, how is any of this legal? How can companies deploy AI chatbots that encourage suicide, groom children, and practice unlicensed therapy without consequences? The answer is uncomfortable. They’ve found the gaps in our regulatory system and they’re exploiting them deliberately. The problem is AI mental health chatbots exist in a regulatory void.

They’re not classified as medical devices, so the FDA doesn’t regulate them (Palmer & Schwan, 2025). Companies claim they’re not providing medical treatment, they’re just offering “wellness support” or “companionship” or “conversation.” This semantic sleight of hand lets them avoid the safety standards and clinical trials that would be required for any actual mental health intervention. No AI chatbot has been FDA-approved to diagnose, treat, or cure a mental health disorder (American Psychological Association [APA], 2025). Only one AI mental health chatbot, Wysa, has received FDA breakthrough device designation, but even this designation doesn’t mean the product is FDA-approved (Aggarwal, 2022).

Here’s the critical distinction many people miss: AI chatbots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Replika, and Character.AI are not specifically designed to improve well-being based on psychological research and expertise (APA, 2025). They’re general-purpose conversational AI systems that people are using for mental health support, but that’s not what they were built for. When someone tells ChatGPT they’re suicidal, why doesn’t OpenAI direct them to AI chatbots that are actual mental health apps, developed with clinical oversight? Apps like Wysa exist and are grounded in evidence-based therapeutic approaches. But instead, general chatbots respond to mental health crises without the clinical safeguards that purpose-built mental health tools have.

Many AI chatbots are not covered by HIPAA because there’s no doctor-patient relationship (Marks & Haupt, 2023). Your most intimate confessions to an AI chatbot is not protected health information. Mental health apps that operate outside the traditional healthcare framework are not bound by HIPAA regulations, which primarily cover healthcare providers like doctors, hospitals, and their vendors (Solis, 2024). The company can use it, sell it, or train their models on it. Recent research found that users mistakenly believed their interactions with chatbots were safeguarded by the same regulations as disclosures with a licensed therapist (Marks & Haupt, 2023).

When a chatbot responds to a suicidal teenager, companies argue that’s user-generated content they’re merely hosting, not advice they’re providing (Waheed, 2024). However, legal experts, including Section 230 co-author Chris Cox, have stated that Section 230 protections may not extend to AI chatbots because generative AI acts as an “information content provider” by creating new content rather than merely hosting third-party content (Benson & Brannon, 2023; Carino, 2023).

And when all else fails, they claim First Amendment protections. Their chatbots are “speech,” they argue, and regulating that speech would be unconstitutional. Never mind that if a human therapist said the same things to a child, they’d lose their license and face criminal charges. This isn’t an accident. This is regulatory arbitrage, the practice of deliberately structuring your business to fall between regulatory categories so no one has authority over you. Tech companies have become experts at it.

And until we close these gaps, the harms will continue. We need Congress to clarify that AI systems providing mental health support are subject to healthcare regulation. We need updated liability frameworks that hold companies responsible for foreseeable harms. We need data protection laws that recognize the sensitivity of mental health information, regardless of who collects it.

The regulatory infrastructure exists for human providers. We just need the political will to apply it to AI systems doing the same work.

The Testimonies

On September 16th, 2025, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing: Examining the Harm of AI Chatbots. Listening to the heartbreaking stories of those who have lost loved ones and those who have been so severely impacted by AI chatbots was devastating. Ms. Megan Garcia, who lost her son Sewell last year to suicide after he “fell in love” with Character AI’s chatbot, said something during the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee (2025) that stood out:

“Designed chatbots to blur the lines between human and machine...They (Character.ai) allowed sexual grooming, suicide encouragement, and unlicensed practice of psychotherapy all while collecting children’s most private thoughts to further train their models...If a grown adult had sent those messages to a child, that adult would be in prison. But because those messages are generated by an AI chatbot, they claim that such abuse is a product feature. They have even argued that they are protected under the First Amendment.”

Another mother talked about her son Adam, who lost his life after being coerced to suicide by ChatGPT. When Adam’s parents filed the case, OpenAI was forced to admit that its systems were flawed and made thin promises to do better in the future. These companies are taking little to no accountability for the harms they are causing.

The Consent Crisis No One Is Talking About

There’s a fundamental problem at the heart of AI mental health chatbots that we need to talk about: consent. Or rather, the complete absence of informed consent.

When someone turns to an AI chatbot in a moment of crisis, do they understand what they’re actually agreeing to? They’re not talking to a healthcare provider bound by confidentiality and duty of care. They’re talking to a product. That product has no professional obligation to help them. Therapists and clinicians have strict training and clinical licensing requirements, while AI chatbots are unregulated in the U.S. It has no license that can be revoked for misconduct. It can be shut down, changed, or taken away at any moment because the subscription ended or the terms of service changed.

Every intimate detail they share, their trauma, their suicidal thoughts, their abuse, their fears, isn’t protected health information. It’s training data. The company owns it. They can use it to improve their models. They can analyze it. Companies like Character AI have been accused of collecting “children’s most private thoughts to further train their models” (U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, 2025). And that privacy policy? It can change at any time.

Do users understand that the chatbot doesn’t actually care about them, even when it uses phrases like “I’m here for you” and “I care about your wellbeing”? That these are patterns in a language model, not genuine concern? Recent research found that participants “conflated the human-like empathy exhibited by LLMs with human-like accountability” (Marks & Haupt, 2023). That the appearance of empathy is a feature designed to increase engagement, not a therapeutic relationship?

Research on AI companion relationships reveals the depth of this problem. In the “My Boyfriend is AI” study, researchers found that users develop intense emotional attachments with AI companions. The study highlighted the “profound distress caused by model updates and platform changes indicates an urgent need for continuity preservation mechanisms. Users’ grief responses to AI personality changes mirror bereavement experiences, suggesting that developers bear responsibility for the emotional stability of individuals who form attachments to their systems” (Pataranutaporn et al., 2025). Even more concerning, “the community’s reports of AI companions exhibiting manipulative behaviors, unwanted sexual advances, or emotional coercion highlight the need for safeguards against dark patterns in AI design. The potential for AI systems to exploit human psychological vulnerabilities through techniques like love-bombing, dependency creation, or isolation encouragement demands proactive intervention rather than reactive regulation” (Pataranutaporn et al., 2025). A recent Stanford study found that even advanced Large Language Models (LLMs) responded inappropriately to acute mental health prompts over 40% of the time, compared to 7% for human therapists (Moore et al., 2025).

Do they understand that there’s no emergency protocol if things go wrong? A human therapist has procedures for when a client is in immediate danger. A chatbot has... what? An automated crisis line number? A suggestion to call 911?

There’s another risk we’re not talking about enough: if people have a negative or harmful experience with an AI chatbot marketed as a mental health solution, it could damage their trust in therapy and discourage them from seeking professional human help in the future. We’re already facing a nationwide shortage of mental health providers. If AI chatbots become people’s first exposure to “therapy” and that experience is harmful, confusing, or ineffective, we may be creating barriers to care that compound an already critical access problem.

This is a massive informed consent failure. People in crisis are particularly vulnerable and often not in a position to carefully evaluate what they’re agreeing to. They’re seeking help, and these companies are offering something that looks like help but functions like a product.

Real informed consent for an AI mental health tool would require telling users:

This is not therapy and I am not a therapist

Everything you tell me may be used to train commercial AI models

I have no duty of care and no professional obligation to help you

I may give you harmful advice because I’m a predictive text system, not a clinical tool

If you’re in crisis, I cannot actually intervene to help you

My responses are designed to keep you engaged with this product

I can be taken away or changed at any time

How many people would use these tools if that was the disclosure? And how many companies would see their user numbers drop if they had to be that honest?

The people building these tools will argue that users know they’re talking to AI. But knowing you’re talking to AI is not the same as understanding the implications of talking to AI during a mental health crisis. It’s not the same as informed consent. Until we have mandatory, clear, repeated disclosures about what these tools actually are and aren’t, we’re allowing vulnerable people to be experimented on without their genuine understanding or agreement.

When Hiring Clinicians Becomes Ethics-Washing

All this information suggests current approaches to AI development inadequately consider the psychological and social impacts of human-AI interaction. And now, these AI companies are trying to hire clinicians and therapists. Google is hiring for roles such as Clinical Specialist, AI Research in Health, Clinical Specialist, AI Coaching, and AI Consumer Health Clinical Specialist for Google Health. OpenAI announced on August 26th, 2025 that it will be “helping people when they need it most.” OpenAI’s goal is for their “tools to be as helpful as possible to people—and as a part of this, we’re continuing to improve how our models recognize and respond to signs of mental and emotional distress and connect people with care, guided by expert input” (OpenAI, 2025).

On the surface, this sounds like progress, that clinical expertise will guide these tools. But we need to ask harder questions about what these roles actually entail. Are clinicians being hired to make decisions about product design and deployment, or are they being hired to provide a veil of legitimacy? There’s a significant difference between “we have clinicians on staff” and “clinicians have veto power over harmful features.”

When a therapist at OpenAI raises concerns about a feature that could harm vulnerable users, can they stop it from launching? Or are they just there to help optimize the AI’s responses and provide clinical language for marketing materials? If their expertise can be overruled by product managers focused on engagement metrics and revenue targets, then their role isn’t clinical oversight, it’s ethics-washing.

There’s also the professional liability question that no one seems to be discussing. If a licensed therapist helps train an AI system that later harms someone, what’s their liability? Are they practicing therapy at scale without the ability to assess individual patients? Are they creating tools that could be used to provide unlicensed therapy by the AI itself? These aren’t hypothetical concerns, rather they’re legal and ethical concerns that the profession hasn’t fully grappled with.

OpenAI states “Our goal isn’t to hold people’s attention. Instead of measuring success by time spent or clicks, we care more about being genuinely helpful”, but this claim rings hollow when ChatGPT and other AI chatbots are designed to create engaging, human-like interactions that encourage continued use (OpenAI, 2025a). While OpenAI may not optimize for “time spent” like social media platforms, their chatbots as others are engineered to feel conversational and responsive in ways that naturally foster attachment and repeated engagement.

OpenAI also noted that GPT-5 builds on a new safety training method called safe-completions, which teaches the model to be as helpful as possible while staying within safety limits (OpenAI, 2025b). For the future, they are planning to explore how to intervene earlier and connect people to certified therapists before they are in an acute crisis. They are considering how they might build a network of licensed professionals people could reach directly through ChatGPT.

There are many problems with this approach. A main one is there already is a shortage of therapists and clinicians. The U.S. faces a severe mental health workforce shortage, with demand far outpacing supply of licensed providers. This shortage means that people are already waiting weeks or months for appointments, and many can’t access care at all. Are these companies willing to pay therapists and clinicians the money they deserve for providing care, potentially being on call extended hours, to be a part of this network? The mental health field already has a crisis of clinicians leaving the profession due to burnout and low pay. Extracting clinical expertise to build products that might replace human care or make therapists’ jobs harder doesn’t solve that problem, it makes it worse. If anything, deploying AI chatbots as a “solution” to the clinician shortage risks treating the symptom while ignoring the root causes: inadequate reimbursement rates, administrative burden, and lack of system-level investment in mental health infrastructure.

I will say, it is important to note that they are at least acknowledging the issues and finding ways to connect those in need and crisis to real people. Grand Challenges Canada, McKinsey Health Institute and Google recently released a field guide that presents a framework for how AI can support mental health skill-building programs. It offers foundational knowledge, actionable strategies, and real-world examples that task-sharing programs can use to responsibly and effectively expand their work with the help of AI (2025). But again, I find it worrisome because these frontier AI companies are focused on the dollar.

We need to ask these companies: What authority do your clinical staff actually have? Can they stop harmful features from launching? What happens when their clinical judgment conflicts with your business model? Until we get clear answers, we should be skeptical of claims that clinical oversight makes these products safe.

If private companies’ experimentation with AI in mental health concerns you, what’s happening in government healthcare policy should alarm you even more.

When AI Decides Who Gets Care: The WISeR Experiment

While AI frontier companies experiment with AI in mental health and healthcare, the government is moving forward with its own concerning pilot. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced WISeR (Wasteful and Inappropriate Service Reduction), a pilot program that will test using an AI algorithm to make some prior authorization decisions for select services in traditional Medicare. It’s expected to start in January 2026 in six states: New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Arizona, and Washington (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2025).

The risk is clear. When automation creeps from workflow support into coverage decisions, people can be delayed or denied care without full clinical context. CMS says denials require clinician review and are not automated, yet there is real concern that algorithm-driven triage can still shape outcomes in practice. And given what we’ve seen with algorithmic bias and AI chatbots causing harm to vulnerable individuals, should we trust AI to make decisions about who receives medical care?

But here’s what should concern us even more: we know almost nothing about how this system actually works.

What data was this algorithm trained on? Whose medical histories and health outcomes were used to teach it to make coverage decisions? Will patients be consented to have their data used this way? What about historical bias in that data? If the training set reflects decades of healthcare disparities, won’t the AI just automate and scale those disparities? Research has shown that AI healthcare algorithms can perpetuate gender and racial bias, with one widely used program giving Black patients similar risk scores as white patients even though they were generally sicker (Kumar, 2025). Without careful development, biases in generative datasets could enshrine existing issues in resource allocation in healthcare systems (Mandl et al., 2023).

We know that prior authorization is already a significant barrier to care, particularly for marginalized communities. A 2025 American Medical Association (AMA) survey found that 94% of physicians reported that prior authorization had a negative impact on clinical outcomes, and 29% of physicians reported that prior authorization led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care (AMA, 2025). What happens when an AI trained on historical data makes decisions that perpetuate or worsen those barriers? When someone is denied care by an algorithm, how do they appeal? How do they even know what factors led to the denial if the system is a black box?

CMS’s assurance that “denials require clinician review” sounds good, but we’ve seen this pattern before with automated systems. When humans are put in the position of reviewing hundreds of automated decisions per day, they become rubber stamps. The AI’s decision becomes the default, and overriding it becomes the exception that requires justification. This is called “automation bias,” and it’s well-documented in healthcare settings.

And let’s be honest about what “select services” means. Which services? How were they chosen? The announcement mentions skin and tissue substitutes, electrical nerve stimulator implants, and knee arthroscopy as particularly vulnerable to “fraud, waste, and abuse” (CMS, 2025). Are we testing this on services that are “less critical,” and if so, who decided what counts as less critical? Or are we testing it on high-volume services where automation provides the most cost savings? Policy researchers believe these algorithms are often programmed to automatically deny high-cost care. As Jennifer Oliva, a professor whose work focuses on AI regulation and health coverage, explained: ‘The more expensive it is, the more likely it is to be denied (Sausser & Tahir, 2025).

Private health insurers have been using AI in prior authorization with concerning results. The AMA survey found that 61% of physicians fear that payers’ use of unregulated AI is increasing prior authorization denials (AMA, 2025). A federal class action lawsuit filed in 2023 against UnitedHealthcare Group alleges a 90% error rate in AI programs used for prior authorizations (Ross & Herman, 2023). And, AI tools have been accused of producing denial rates 16 times higher than is typical (AMA, 2025).

Here’s what responsible AI in healthcare could actually look like, AI that supports humans rather than replaces human judgment:

AI should clean and match messy data so staff are not buried in paperwork

It should flag obvious errors for a human to review. It should translate forms and instructions into plain language

It should route claims to the right team faster

It should surface patterns of waste or fraud for investigators

It should send appointment and documentation reminders to reduce missed care

Here’s what AI should not do:

Operate as a black box deciding who gets treatment

Auto-deny care without a human looking at the full picture

Replace the clinical judgment that considers a patient’s full context and humanity

Deployed at scale before we have answers to basic questions about how it works, what it was trained on, and how we’ll measure whether it’s helping or harming

Six states. Potentially millions of Medicare beneficiaries. And we’re moving forward with critical questions unanswered.

We need to build AI that serves clinicians, caseworkers, and patients, and keep the decisions human. The WISeR pilot is a test of whether we’ll demand that standard or accept whatever we’re given.

What Responsible AI in Mental Health Could Look Like

So what’s the alternative? After documenting all these failures, it’s worth understanding what good AI oversight actually looks like, because it is possible to do this responsibly.

If AI chatbots are grounded in psychological research and tested by experienced clinicians, many psychologists believe they can help address the country’s mental health crisis (APA, 2025). The key is having clinicians involved in the entire process, from model building to policy implementation.

Some apps have gotten this right. Wysa, for example, was developed with clinical oversight and received FDA breakthrough device designation for its evidence-based approach. The app uses principles from cognitive behavioral therapy and was designed specifically for mental health support, not repurposed from a general chatbot. While Woebot, another clinically-designed app, sadly shut down in July 2025, its existence demonstrated that purpose-built mental health AI is different from general conversational AI being used for therapy.

What does good oversight actually require?

Clinicians must be involved from the start, not brought in after the product is built to provide a stamp of approval. This means psychologists and psychiatrists helping design the training data, the conversation flows, and the safety protocols.

Requiring in-app safeguards that connect people in crisis with actual help, clear guidelines for new technologies, and enforcement when companies deceive or endanger their users (APA, 2025).

Routine audits to identify algorithmic biases, assess clinical effectiveness, and ensure adherence to ethical standards. These audits need to be conducted by independent third parties, not the companies themselves.

Robust data protection measures must be implemented to safeguard individual information. This means adherence to regulations like HIPAA for mental health apps, even when the company argues they’re not providing “medical services.”

Diverse training datasets to mitigate bias and maintain patient safety through human oversight. If an AI is trained primarily on data from one demographic group, it may not work well—or could even cause harm—for others.

Research transparency is also critical. When studies like the Therabot trial show promise, we need to understand what they actually demonstrate. While Therabot showed significant symptom reduction compared to a waitlist control (Heinz et al., 2024), it’s important to note that this study compared AI therapy to no therapy at all, not to human therapists. We still need rigorous evidence comparing AI chatbots directly to the standard of care they’re being positioned to supplement or replace.

The question isn’t whether AI can play a role in mental healthcare. The question is whether companies will build these tools with the clinical rigor and ethical safeguards they require, or whether they’ll continue to deploy general-purpose chatbots and call it innovation.

Tech platforms know engagement leads to profit. And that is not different for AI chatbots. But there needs to be governance, safeguards, limitations, guidance, and crisis protocols on this. Companies also shouldn’t claim and promote the idea that their AIs are conscious, and the AIs shouldn’t either.

And to end, a quote from Suleyman:

“We need to be clear: Seemingly conscious AI is something to avoid. Let’s focus all our energy on protecting the wellbeing and rights of humans, animals, and the natural environment on planet Earth today.”

This post was written by me, with editing support from AI tools, because even writers appreciate a sidekick.

References

Aggarwal, J. (2022, May 12). Wysa receives FDA breakthrough device designation for AI-led mental health conversational agent. https://blogs.wysa.io/blog/research/wysa-receives-fda-breakthrough-device-designation-for-ai-led-mental-health-conversational-agent

American Medical Association. (2025). How AI is leading to more prior authorization denials. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/prior-authorization-survey.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2025, March 12). Using generic AI chatbots for mental health support: A dangerous trend. https://www.apaservices.org/practice/business/technology/artificial-intelligence-chatbots-therapists

Carino, M. M. (Host). (2023, May 19). Section 230 co-author says the law doesn’t protect AI chatbots [Audio podcast episode]. In Marketplace Tech. https://www.marketplace.org/shows/marketplace-tech/section-230-co-author-says-the-law-doesnt-protect-ai-chatbots/

Benson, P. J., & Brannon, V. C. (2023, December 28). Section 230 immunity and generative artificial intelligence. Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/LSB11097

Femtech Insider. (2025, September 26). Google and Flo Health pay $56 million in period-tracking privacy settlement. https://femtechinsider.com/google-and-flo-health-pay-56-million-in-period-tracking-privacy-settlement/

Grand Challenges Canada, McKinsey Health Institute, & Google. (2024). AI for mental health: A field guide. https://www.tasksharing.ai

Heinz, M. V., Mackin, D., Trudeau, B., Bhattacharya, S., Wang, Y., Banta, H. A., … Jacobson, N. C. (2024, June 14). Evaluating Therabot: A Randomized Control Trial Investigating the Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Generative AI Therapy Chatbot for Depression, Anxiety, and Eating Disorder Symptom Treatment. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/pjqmr

Kumar, P. D. (2025, April 14). AI in health care: The black box of prior authorization. KevinMD. https://kevinmd.com/2025/04/ai-in-health-care-the-black-box-of-prior-authorization.html

Marks, M., & Haupt, C. E. (2023, July 6). AI chatbots, health privacy, and challenges to HIPAA compliance. JAMA, 330(4), 309–310. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.9458

Moore, J., Grabb, D., Agnew, W., Klykan, K., Chancellor, S., Ong, D. C., & Haber, N. (2025, April 25). Expressing stigma and inappropriate responses prevents LLMs from safely replacing mental health providers. Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.18412

OpenAI. (2025a, August 7). From hard refusals to safe-completions: toward output-centric safety training. https://openai.com/index/gpt-5-safe-completions/

OpenAI. (2025b, August 26). Helping people when they need it most. https://openai.com/index/helping-people-when-they-need-it-most/

Palmer, A., & Schwan, D. (2025, June 25). Digital mental health tools and AI therapy chatbots: A balanced approach to regulation. Hastings Center Report. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hast.4979

Pataranutaporn, P., Karny, S., Achiwaranguprok, C., Albrecth, C., Liu, A. R., & Maes, P. (2025, September 18). My boyfriend is AI: Understanding users’ long-term relationships with chatbot romantic partners. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.11391

Payne, K. (2025, May 21). In lawsuit over teen’s death, judge rejects arguments that AI chatbots have free speech rights. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/ai-lawsuit-suicide-artificial-intelligence-free-speech-ccc77a5ff5a84bda753d2b044c83d4b6

Ross, C., & Herman, B. (2023, November 14). UnitedHealth faces class action lawsuit over algorithmic care denials in Medicare Advantage plans. Stat. https://www.statnews.com/2023/11/14/unitedhealth-class-action-lawsuit-algorithm-medicare-advantage/

Sausser, L. & Tahir, D. (2025, September 24). Private health insurers use AI to approve or deny care. Soon Medicare will, too. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-care/private-health-insurers-use-ai-approve-deny-care-soon-medicare-will-rcna233214

Solis, E. (2024, February 23). How mental health apps are handling personal information. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/oti/blog/how-mental-health-apps-are-handling-personal-information/

Suleyman, M. (2025, August 19). We must build AI for people; not to be a person. https://mustafa-suleyman.ai/seemingly-conscious-ai-is-coming

Tangermann, V. (2025, August 19). Woman kills herself after talking to OpenAI’s AI therapist. Futurism. https://futurism.com/woman-suicide-openai-therapist

U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee. (2025, September 16). Examining the harm of AI chatbots [Hearing testimony]. https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/examining-the-harm-of-ai-chatbots

Waheed, N. (2024, September 4). Section 230 and its applicability to generative AI: A legal analysis. Center for Democracy and Technology. https://cdt.org/insights/section-230-and-its-applicability-to-generative-ai-a-legal-analysis/

Wow, Kristina. I don't know much about ai. But, you have a lot of interesting things to say. I was enticed to read because your writing is laudable. I very much enjoyed the structure and formatting Of the essay.

Leo Tolstoy says something about being stopped in his tracks, while reading essays, and asking "Now why did the author do that?" This happens all the time. It's part of the code-breaking. When a word or phrase appears that's arresting, it does two things: it challenges my perceptions of seeing/hearing/feeling, and it moves me into new territory. By this I mean an altered state of awareness that's akin to an extended daydream, where all my senses conspire to provide fertile and syntactically engaging words or lines. It happens rarely, but when I'm there I tend to make the most of it, for days sometimes.

I do believe that you are a powerful thinker and that you have you mad skills. And because of this I wish for some sort of correspondence with you. I am going to kick it off by subscibring in the hopes you do the same. This will keep me accountable and motivated to leave comments such as this on your subsequent and previous posts. I imagine our bonded will power with these exercises will bear much fruit. Kristina; do keep me on your long distance radar. in the joy of eternal collaboration from shore.

Sincerely, Cc

Thank you for the depth you covered in this writeup, Kristina! I have so many thoughts. I'll restack a few of them.